JSA #45: The Trial of Kobra

All this week has been Kobra Week over at Dave's Long Box, so now seems a good a time as any to take a look at one of the final Kobra stories, when Lord Naga finally saw his day in court.

In JSA #10, supervillain terrorist Kobra blew up Lexair Flight #178, killing 217 people (including Atom Smasher's mother). In #45, almost three years later, he finally got his day in court. This time lapse, stated to be eleven months in DCU time, is probably the most realistic legal aspect of the story, as major cases often take many months to go to trial. But for readers of a monthly comic, it read like a loose end that dangled for three years until being resolved.

That court is shown to be the U.S. District Court in New York City. NYC is actually the home to two federal district courts: the Eastern District of New York (headquartered in Brooklyn) and the Southern District (in Manhattan). Not being a New Yorker, and lacking any images of either courthouse, I’m at a loss as to whether the art accurately reflects either building. But blowing up an airliner is a good way to get the feds on your case, so federal court is the right place for the trial to be.

A news reporter tells us three of the charges Kobra is facing: “first degree murder, conspiracy to commit an international act of terrorism, use of a weapon of mass destruction.” Hopefully those aren’t the only three, but at least the first and third are legitimate federal crimes. And I'll guess that the second charge is referring to this.

It’s never stated outright, but most of the dialogue and circumstances in the issue points to this being the first day of the trial, or at least very early in the proceedings (as Wildcat puts it, “We’re just settling in to watch the big circus go down” right after Jakeem Thunder said "I can't believe we're actually watching this. About time..."). There is only one actual trial scene, spanning pages 7 and 8.

Those two pages appear to make one of those mistakes that courtroom dramas should never, under any circumstances, make: the prosecution calling the defendant as a witness. And on what seems to be the first day of trial, no less. The prosecution can never call a defendant to the stand. Never. That's at the haert of the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Major, unforgivable flub there, and the entire trial scene is dependent on this error.

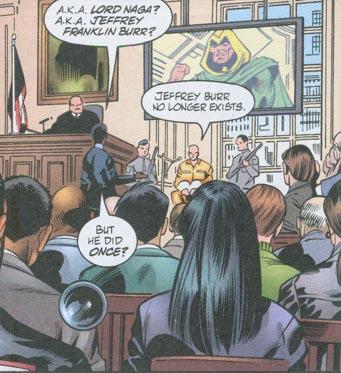

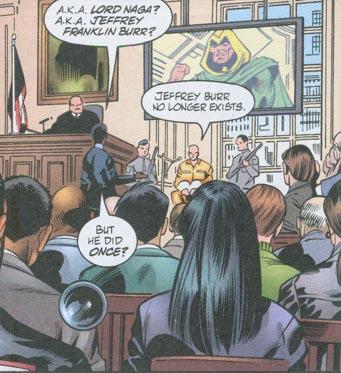

Leonard Kirk makes the same mistake with Kobra as was made with the Shadow Thief in Manhunter, portraying the defendant in an orange jailhouse jumpsuit, wearing massive high-tech shackles on his wrists. Such an appearance is extraordinarily prejudicial to the defense, as are the armed guards flanking the witness stand. Perhaps Kobra himself chose not to wear any better clothes, but the shackles and guns are very much out of line.

There’s also that 10-foot screen hanging above the witness stand that shows Kobra in his full supervillain get-up. That crosses the line from legally erroneous to simply absurd. There’s nothing in a real court that resembles that in the slightest. Imagine if during the Michael Jackson trial there had been a giant portrait of Jacko hanging on the wall of the courtroom, in full 'Thriller' get-up.

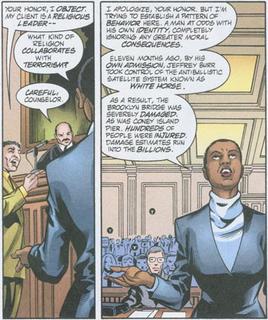

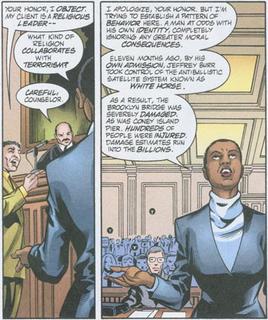

The prosecutor begins with questioning Kobra about his name, to which Kobra replies “Jeffrey Burr no longer exists,” and the prosecutor responds “But he did once?” At this point, the defense attorney stands and says “I object, my client is a religious leader--.” This is wrong for two reasons. First, that’s not a real objection. Being a religious leader might be relevant if the question inquired into privileged information (such as asking a priest about a confidential confession), but that’s certainly not the case here. That leads to the second problem with the objection, which is that it’s not at all clear what he’s objecting to. Kobra being a religious leader does not seem to bear any relation to a name question, or at least not in any way that’s objectionable. I’m at a loss as to how the question is objectionable at all.

Then again, the defense attorney does get cut off, so maybe he had a better objection that he didn’t get to finish. That’s a problem in itself. The prosecutor interrupted, we never heard a full objection, and the judge never ruled on the objection before the prosecutor continued with the examination. Judges always rule on objections, and to do so, he would’ve had the defense attorney finish.

After interrupting the objection, the prosecutor goes into a long-winded narrative providing tons of expository details about the case against Kobra and the evils he’s committed. Now that’s clearly objectionable. It’s not a question, it’s testimony, and testimony is supposed to come from witnesses, not the attorney. Strangely, there’s no objection from the defense on that.

The prosecutor also mentions in passing that “by his own admission,” Kobra committed these acts of terrorism. Since there was no objection, then if he wasn’t denying his participation, I'm left scratching my head as to what the defense’s strategy was going to be. Insanity? Some sort of bizarre religious justification?

There’s nothing remarkable about the rest of the questioning, though Mr. Terrific’s comment afterward that Kobra is “good…about as charismatic as they come,” seems very odd. Kobra’s comments on the stand are overtly threatening to Americans ("I reject your nation's sovereignty....A great darkness will spread its wings over creation."), and the jurors appear genuinely troubled, not charmed.

Finally, an explosion occurs outside the courthouse, and the courtroom bursts into chaos. A half dozen federal officials train their guns on Kobra, and the press cameramen (seen in the background of earlier panels) spill out of their box to catch the moment upclose on film. Kobra eventually speaks, saying “Now that I have the world’s attention, allow me to explain,” and proceeding to say that if he isn’t set free, five hundred of his followers outside the courthouse will be killed immediately.

State courts sometimes allow television coverage of trials, often at the judge’s discretion. But this is a federal court, and television cameras have been expressly forbidden from covering federal criminal trials since 1946. The reasons for this are said to be that cameras distract trial participants, unfairly affect the outcome, and lessen the court’s dignity. Unless the DCU gov’t adopted a very different rule, Wildcat should not be watching this trial on TV and Kobra should not have the world’s attention.

That’s it for the legal analysis, but there’s a political aspect to the ending I have to comment on. In response to the threat to the 500 lives outside, Mr. Bones and the judge agree to let Kobra walk free. This is a straightforward submission to a terrorist’s demands (and in front of live television cameras, no less). It has been the policy of the U.S. government for decades to never give in to terrorist demands. To do so may spare some lives in the present, but it endangers innumerable lives in the future. And as a result of this philosophy, America has been relatively free of high-stakes terrorist demands, in large part because it’s understood that we will never acquiesce in those demands.

Here, though, Kobra made a straightforward terrorist demand ("Set me free or hundreds will die"), and the US conceded and complied with it. We can't even be certain that the 500 were saved as a result, since they were all teleported away. With this action, though, the DCU opened itself up to the risk of future villains pulling the exact same stunt Kobra did to avoid punishment. And unless they appease each one, then sooner or later innocent people will die.

In JSA #10, supervillain terrorist Kobra blew up Lexair Flight #178, killing 217 people (including Atom Smasher's mother). In #45, almost three years later, he finally got his day in court. This time lapse, stated to be eleven months in DCU time, is probably the most realistic legal aspect of the story, as major cases often take many months to go to trial. But for readers of a monthly comic, it read like a loose end that dangled for three years until being resolved.

That court is shown to be the U.S. District Court in New York City. NYC is actually the home to two federal district courts: the Eastern District of New York (headquartered in Brooklyn) and the Southern District (in Manhattan). Not being a New Yorker, and lacking any images of either courthouse, I’m at a loss as to whether the art accurately reflects either building. But blowing up an airliner is a good way to get the feds on your case, so federal court is the right place for the trial to be.

A news reporter tells us three of the charges Kobra is facing: “first degree murder, conspiracy to commit an international act of terrorism, use of a weapon of mass destruction.” Hopefully those aren’t the only three, but at least the first and third are legitimate federal crimes. And I'll guess that the second charge is referring to this.

It’s never stated outright, but most of the dialogue and circumstances in the issue points to this being the first day of the trial, or at least very early in the proceedings (as Wildcat puts it, “We’re just settling in to watch the big circus go down” right after Jakeem Thunder said "I can't believe we're actually watching this. About time..."). There is only one actual trial scene, spanning pages 7 and 8.

Those two pages appear to make one of those mistakes that courtroom dramas should never, under any circumstances, make: the prosecution calling the defendant as a witness. And on what seems to be the first day of trial, no less. The prosecution can never call a defendant to the stand. Never. That's at the haert of the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Major, unforgivable flub there, and the entire trial scene is dependent on this error.

Leonard Kirk makes the same mistake with Kobra as was made with the Shadow Thief in Manhunter, portraying the defendant in an orange jailhouse jumpsuit, wearing massive high-tech shackles on his wrists. Such an appearance is extraordinarily prejudicial to the defense, as are the armed guards flanking the witness stand. Perhaps Kobra himself chose not to wear any better clothes, but the shackles and guns are very much out of line.

There’s also that 10-foot screen hanging above the witness stand that shows Kobra in his full supervillain get-up. That crosses the line from legally erroneous to simply absurd. There’s nothing in a real court that resembles that in the slightest. Imagine if during the Michael Jackson trial there had been a giant portrait of Jacko hanging on the wall of the courtroom, in full 'Thriller' get-up.

The prosecutor begins with questioning Kobra about his name, to which Kobra replies “Jeffrey Burr no longer exists,” and the prosecutor responds “But he did once?” At this point, the defense attorney stands and says “I object, my client is a religious leader--.” This is wrong for two reasons. First, that’s not a real objection. Being a religious leader might be relevant if the question inquired into privileged information (such as asking a priest about a confidential confession), but that’s certainly not the case here. That leads to the second problem with the objection, which is that it’s not at all clear what he’s objecting to. Kobra being a religious leader does not seem to bear any relation to a name question, or at least not in any way that’s objectionable. I’m at a loss as to how the question is objectionable at all.

Then again, the defense attorney does get cut off, so maybe he had a better objection that he didn’t get to finish. That’s a problem in itself. The prosecutor interrupted, we never heard a full objection, and the judge never ruled on the objection before the prosecutor continued with the examination. Judges always rule on objections, and to do so, he would’ve had the defense attorney finish.

After interrupting the objection, the prosecutor goes into a long-winded narrative providing tons of expository details about the case against Kobra and the evils he’s committed. Now that’s clearly objectionable. It’s not a question, it’s testimony, and testimony is supposed to come from witnesses, not the attorney. Strangely, there’s no objection from the defense on that.

The prosecutor also mentions in passing that “by his own admission,” Kobra committed these acts of terrorism. Since there was no objection, then if he wasn’t denying his participation, I'm left scratching my head as to what the defense’s strategy was going to be. Insanity? Some sort of bizarre religious justification?

There’s nothing remarkable about the rest of the questioning, though Mr. Terrific’s comment afterward that Kobra is “good…about as charismatic as they come,” seems very odd. Kobra’s comments on the stand are overtly threatening to Americans ("I reject your nation's sovereignty....A great darkness will spread its wings over creation."), and the jurors appear genuinely troubled, not charmed.

Finally, an explosion occurs outside the courthouse, and the courtroom bursts into chaos. A half dozen federal officials train their guns on Kobra, and the press cameramen (seen in the background of earlier panels) spill out of their box to catch the moment upclose on film. Kobra eventually speaks, saying “Now that I have the world’s attention, allow me to explain,” and proceeding to say that if he isn’t set free, five hundred of his followers outside the courthouse will be killed immediately.

State courts sometimes allow television coverage of trials, often at the judge’s discretion. But this is a federal court, and television cameras have been expressly forbidden from covering federal criminal trials since 1946. The reasons for this are said to be that cameras distract trial participants, unfairly affect the outcome, and lessen the court’s dignity. Unless the DCU gov’t adopted a very different rule, Wildcat should not be watching this trial on TV and Kobra should not have the world’s attention.

That’s it for the legal analysis, but there’s a political aspect to the ending I have to comment on. In response to the threat to the 500 lives outside, Mr. Bones and the judge agree to let Kobra walk free. This is a straightforward submission to a terrorist’s demands (and in front of live television cameras, no less). It has been the policy of the U.S. government for decades to never give in to terrorist demands. To do so may spare some lives in the present, but it endangers innumerable lives in the future. And as a result of this philosophy, America has been relatively free of high-stakes terrorist demands, in large part because it’s understood that we will never acquiesce in those demands.

Here, though, Kobra made a straightforward terrorist demand ("Set me free or hundreds will die"), and the US conceded and complied with it. We can't even be certain that the 500 were saved as a result, since they were all teleported away. With this action, though, the DCU opened itself up to the risk of future villains pulling the exact same stunt Kobra did to avoid punishment. And unless they appease each one, then sooner or later innocent people will die.

<< Home