She-Hulk #4: Web of Lies

She-Hulk #4

Writer: Dan Slott

Artist: Juan Bobillo

Synopsis: Pug and Jen convince Spider-Man to sue J. Jonah Jameson (and the Daily Bugle) for libel. At trial, they call John Jameson, Betty Brant, Robbie Robertson, and more as witnesses to testify to Jonah’s history of printing lies about Spider-Man in the Bugle. After a brief interruption by the Scorpion, Pug calls Peter Parker to the stand, and after a few questions, announces that he’s adding Parker as a defendant in the case. The next morning, Spider-Man tells Pug and Jen that he wants to settle, and instead of asking for money, he merely asks that Jonah and Peter have to hand out apologies in public, while dressed in chicken suits.

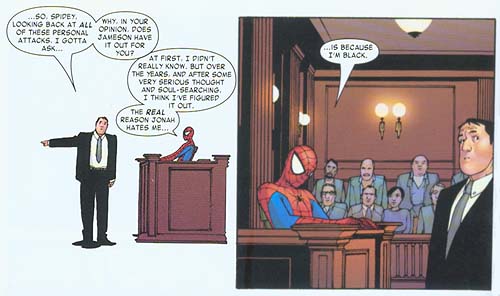

Analysis: It’s an question Spider-fans have postulated for years. With all the horrible things that J. Jonah Jameson has printed about Spider-Man in the Bugle, would Spider-Man have a valid libel claim?

Now, anyone who’s seen the first Spider-Man movie remembers that slander is spoken; in print, it’s libel. The allegation of libel involves the charge that the defendant has been printing harmful lies about the plaintiff. We certainly have that here, given all the incidents over the years where Jonah has implicated Spider-Man as a criminal, as cited in the story.

The story also has Pug point out the second-most important aspect of a libel case such as this. As the trial starts, Pug says “They’re gonna keep pushing how, by wearing the tights, he’s making himself a public figure…but that don’t give ‘em the right to print flat-out lies…”

The law has two different standards for libel. One is for ordinary, private individuals like most of us. Merely printing injurious false statements about a private person can be enough to substantiate a libel claim.

But there’s a higher standard for public figures, those persons “involved in issues in which the public has a justified and important interest.” Public figures are naturally more newsworthy, and when one is the subject of media attention, it’s possible for false statements to accidentally slip past the editors. And when mistakes happen, public figures are more capable of countering such false statements than us normal folk.

So when it comes to libel and public figures, the courts require that the defendant have demonstrated some actual malice in printing the false material. Making a mistake isn’t enough; the defendant generally must have had good reason to know that what they were printing was a lie, and went ahead with it anyway just to hurt the plaintiff.

The comic doesn’t dwell on the issue, but I think it’s fair to declare that Spider-Man is a public figure. He is definitely someone in whom “the public has a justified and important interest.” So Pug and Jen have to show that Jonah printed all those anti-Spider-Man stories maliciously.

And frankly, based on Jonah’s history, I don’t think that would be much of a problem for them. The testimony Pug gets from Betty and Robbie and a police officer does a great job of illustrating the kind of intentional malice that Jonah had toward Spider-Man. Betty’s testimony (“He told me he wanted to pin [Dr. Doom’s attack] on Spider-Man.”) is particularly good in this respect.

Unfortunately, Jonah’s defense doesn’t seem as strong as Pug’s prosecution. Jonah’s lawyer seems more concerned with pointing out Spider-Man’s past troubles than in actually rebutting the evidence of malice. Maybe his point was to imply to the jury that Spider-Man’s history justified Jonah’s overt and intentional lies about Spider-Man’s other activities. It doesn’t strike me as a very strong defense, but then again, Jonah did pretty much do exactly what Pug’s accused him of doing, so there’s not a lot to work with.

Naturally, there were various other mistakes in the issue. The biggest one, and the one most harmful to the plot, is when Pug adds Peter as a defendant mid-trial. Can’t be done. It’s as simple as that. Imagine the situation from Peter’s perspective (and we need to do this as the court treats it, where Peter and Spider-Man are not related persons). The plaintiff has already called several witnesses, and Peter’s had no opportunity to cross-examine any of them. He’s had no time to look at evidence, or gather evidence of his own, or even to hire an attorney. There’s been a whole day of trial that he hasn’t even been privy to. He just shows up to testify in a normal court case, and is suddenly informed that the plaintiff wants to put him on trial too, starting immediately. It brings the case to a quick end, but it’s a legally absurd and impossible plot device.

(Not to mention that if Pug had proposed this earlier in the litigation, while it was still possible to add Peter as a defendant, it would be Spider-Man’s call, not Pug’s, as to whether Peter should be added. If Spider-Man said ‘no,’ Pug would have to oblige.)

The trial also flip-flops on who’s presenting their case. Pug calls several witnesses, then Jonah’s lawyer calls Jonah, then Pug calls Peter. I suppose Pug could be calling Peter as a rebuttal witness, but I can’t imagine why. And because this is a civil suit, Pug would’ve called Jonah as a witness himself, and wouldn’t have waited for the defense to do so.

Maybe the law is different in New York, but here in Georgia, we don’t normally use process servers to deliver subpoenas to witnesses. It’s possible if the witness is stubborn and refuses to cooperate, but that’s not the case with John Jameson or Peter Parker, so their subpoenas should have just been mailed to their homes.

And it’s petty, but it seems that Jonah got special permission to smoke in a New York City courtroom.

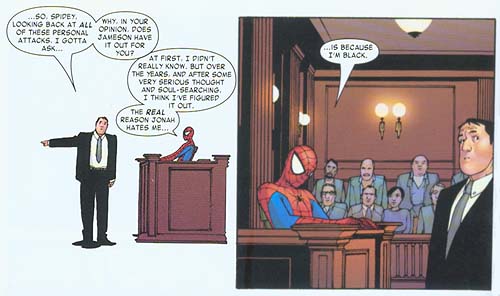

Finally, Jonah makes an excellent point when Spider-Man is called to the stand: how can the court know that the masked guy on the witness stand is actually the authentic Spider-Man? Masked superheroes testifying on the stand is a conceit that’s rather hard to justify under real-world law, but Slott concocts a decent enough explanation. Pug uses an Avengers scanner to verify Spider-Man’s identity through a federal database. I’m not sure the method would hold up under scrutiny (especially given Spidey’s history with clones), but I like the conceit so much that I’ll give it a pass. The fact that the Avengers have ties to the federal government lends the method some added credibility that, say, the Superbuddies wouldn’t be entitled to. And it’s a lot better than Jeph Loeb’s method in the “Challengers of the Unknown” mini-series, where Superman verifies his identity by lifting the jury box.

Previous She-Hulk (Vol. 1) Reviews

She-Hulk #1 (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #2 (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #2b (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #3 (Vol. 1)

Writer: Dan Slott

Artist: Juan Bobillo

Synopsis: Pug and Jen convince Spider-Man to sue J. Jonah Jameson (and the Daily Bugle) for libel. At trial, they call John Jameson, Betty Brant, Robbie Robertson, and more as witnesses to testify to Jonah’s history of printing lies about Spider-Man in the Bugle. After a brief interruption by the Scorpion, Pug calls Peter Parker to the stand, and after a few questions, announces that he’s adding Parker as a defendant in the case. The next morning, Spider-Man tells Pug and Jen that he wants to settle, and instead of asking for money, he merely asks that Jonah and Peter have to hand out apologies in public, while dressed in chicken suits.

Analysis: It’s an question Spider-fans have postulated for years. With all the horrible things that J. Jonah Jameson has printed about Spider-Man in the Bugle, would Spider-Man have a valid libel claim?

Now, anyone who’s seen the first Spider-Man movie remembers that slander is spoken; in print, it’s libel. The allegation of libel involves the charge that the defendant has been printing harmful lies about the plaintiff. We certainly have that here, given all the incidents over the years where Jonah has implicated Spider-Man as a criminal, as cited in the story.

The story also has Pug point out the second-most important aspect of a libel case such as this. As the trial starts, Pug says “They’re gonna keep pushing how, by wearing the tights, he’s making himself a public figure…but that don’t give ‘em the right to print flat-out lies…”

The law has two different standards for libel. One is for ordinary, private individuals like most of us. Merely printing injurious false statements about a private person can be enough to substantiate a libel claim.

But there’s a higher standard for public figures, those persons “involved in issues in which the public has a justified and important interest.” Public figures are naturally more newsworthy, and when one is the subject of media attention, it’s possible for false statements to accidentally slip past the editors. And when mistakes happen, public figures are more capable of countering such false statements than us normal folk.

So when it comes to libel and public figures, the courts require that the defendant have demonstrated some actual malice in printing the false material. Making a mistake isn’t enough; the defendant generally must have had good reason to know that what they were printing was a lie, and went ahead with it anyway just to hurt the plaintiff.

The comic doesn’t dwell on the issue, but I think it’s fair to declare that Spider-Man is a public figure. He is definitely someone in whom “the public has a justified and important interest.” So Pug and Jen have to show that Jonah printed all those anti-Spider-Man stories maliciously.

And frankly, based on Jonah’s history, I don’t think that would be much of a problem for them. The testimony Pug gets from Betty and Robbie and a police officer does a great job of illustrating the kind of intentional malice that Jonah had toward Spider-Man. Betty’s testimony (“He told me he wanted to pin [Dr. Doom’s attack] on Spider-Man.”) is particularly good in this respect.

Unfortunately, Jonah’s defense doesn’t seem as strong as Pug’s prosecution. Jonah’s lawyer seems more concerned with pointing out Spider-Man’s past troubles than in actually rebutting the evidence of malice. Maybe his point was to imply to the jury that Spider-Man’s history justified Jonah’s overt and intentional lies about Spider-Man’s other activities. It doesn’t strike me as a very strong defense, but then again, Jonah did pretty much do exactly what Pug’s accused him of doing, so there’s not a lot to work with.

Naturally, there were various other mistakes in the issue. The biggest one, and the one most harmful to the plot, is when Pug adds Peter as a defendant mid-trial. Can’t be done. It’s as simple as that. Imagine the situation from Peter’s perspective (and we need to do this as the court treats it, where Peter and Spider-Man are not related persons). The plaintiff has already called several witnesses, and Peter’s had no opportunity to cross-examine any of them. He’s had no time to look at evidence, or gather evidence of his own, or even to hire an attorney. There’s been a whole day of trial that he hasn’t even been privy to. He just shows up to testify in a normal court case, and is suddenly informed that the plaintiff wants to put him on trial too, starting immediately. It brings the case to a quick end, but it’s a legally absurd and impossible plot device.

(Not to mention that if Pug had proposed this earlier in the litigation, while it was still possible to add Peter as a defendant, it would be Spider-Man’s call, not Pug’s, as to whether Peter should be added. If Spider-Man said ‘no,’ Pug would have to oblige.)

The trial also flip-flops on who’s presenting their case. Pug calls several witnesses, then Jonah’s lawyer calls Jonah, then Pug calls Peter. I suppose Pug could be calling Peter as a rebuttal witness, but I can’t imagine why. And because this is a civil suit, Pug would’ve called Jonah as a witness himself, and wouldn’t have waited for the defense to do so.

Maybe the law is different in New York, but here in Georgia, we don’t normally use process servers to deliver subpoenas to witnesses. It’s possible if the witness is stubborn and refuses to cooperate, but that’s not the case with John Jameson or Peter Parker, so their subpoenas should have just been mailed to their homes.

And it’s petty, but it seems that Jonah got special permission to smoke in a New York City courtroom.

Finally, Jonah makes an excellent point when Spider-Man is called to the stand: how can the court know that the masked guy on the witness stand is actually the authentic Spider-Man? Masked superheroes testifying on the stand is a conceit that’s rather hard to justify under real-world law, but Slott concocts a decent enough explanation. Pug uses an Avengers scanner to verify Spider-Man’s identity through a federal database. I’m not sure the method would hold up under scrutiny (especially given Spidey’s history with clones), but I like the conceit so much that I’ll give it a pass. The fact that the Avengers have ties to the federal government lends the method some added credibility that, say, the Superbuddies wouldn’t be entitled to. And it’s a lot better than Jeph Loeb’s method in the “Challengers of the Unknown” mini-series, where Superman verifies his identity by lifting the jury box.

Previous She-Hulk (Vol. 1) Reviews

She-Hulk #1 (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #2 (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #2b (Vol. 1)

She-Hulk #3 (Vol. 1)

<< Home