She-Hulk #2

Writer: Dan Slott

Artist: Juan Bobillo

Synopsis: Jen Walters (aka She-Hulk) has her first day of work at Goodman, Lieber, Kurtzberg, & Holliway, and also takes on her first client. His name is Dan Jermain, and he was a Roxxon safety inspector who was knocked into a radioactive vat, from which he emerged as the atomic superman Danger Man. Dan wants to sue Roxxon for the changes he underwent, and the toll that's been taken on his life and marriage. In the end, Jen obtains an $85 million settlement.

Analysis: In this issue, Slott really starts having fun with the oddball aspects of superhuman legal practice. Salvage rights involving Atlanteans, territorial disputes among the Moloids, etc.

The biggest goof comes in the form of the introduction of what became an ongoing element of the series, the law office library's "long boxes." Since Marvel Comics exist as licensed products in the Marvel Universe, and since they still bore the seal of the Comics Code Authority until 2002, then they are deemed legal documents and are automatically admissible in court. It's a clearly preposterous notion, but it's so charming that it can't be frowned upon.

Besides, Jen implies at one point that the events depicted in the comics were all true events, merely adapted into printed form. Given that they're 'real' events, an attorney could still use them to bolster his argument. It would just be a bit more work-intensive than citing a comic book.

Slott does a good job of demonstrating how a superhero origin isn't necessarily all it's cracked up to be. Dan may be an atomic superman, but he's just a working class guy without any interest in dressing up and fighting crime. Imagine 'Bob Parr' from

The Incredibles, without the costume.

We're provided with glimpses of how Dan's life has changed. He's uncomfortable in public. People on the subway stare at him suspiciously. His super-hearing picks up everyone's whispers. He's outgrown all his old clothes, and he regularly rips his new ones. His house is falling apart because every agitated motion can result in a broken door or a hole in the wall. He's lost his insurance because they refuse to cover superhumans. He nearly killed his wife when he rolled over in bed, but she still ended up with broken bones. His marriage is fraying at the edges, and his daughter resents him. Not to mention that he appears to have a permanent glow about his head and hands.

So yes, I think there's a good argument to be made that Dan's life has been negatively impacted by the accident. Granted, it might be a hard sell to a jury full of people who think it'd be swell to be superpowered, but it's surprising the Roxxon lawyers don't seem to even acknowledge the personal damage done.

It crossed my mind to wonder why Dan's complaint wasn't being handled through an ordinary worker's compensation claim. I think that that might be the right situation for the Roxxon lawyers to respond as negatively as they did. Worker's compensation typically exists for measurable physical and medical damages, not for personal and emotional suffering. In such a forum where the question is always "How much were you hurt?," it would be reasonable to say that making a person stronger doesn't merit a recovery.

I do have to take issue with Jen's proposed method of proving damages. She suggests to Dan that they employ the Jean Grey precedent, and suggest that Dan Jermain died when Danger Man was born. This suggestion totally changes the nature of Dan's claim against Roxxon, turning it into a wrongful death claim. It's not a terrible idea, and it could definitely be applicable in the context of certain origins (see Swamp Thing, Will Peyton Starman). Sometimes a character is completely remade by his origin.

However, I don't consider it very persuasive in Dan's case. Dan has been changed physically, but he's clearly the same person inside. He still feels the same way about his wife and daughter, and they still view him as the same man. In fact, his wife is outraged at Jen's suggestion that he's not the same person. His mind wasn't erased and recreated, and his fall into the radioactive vat didn't produce a second body and leave the first one to decay. Unlike the hybernating "real body" of the Jean Grey precedent, Dan specifically states earlier in the issue that he felt his body changing. He's the same mind in the same physical body (albeit an amped-up body), and that's something that the defense would lean on and the jury would see. Jen may be keen on it, but I don't see a wrongful death claim working here.

Plus, if it's determined that Dan Jermain

did die when he fell into the vat, then Worker's Compensation should come back into play. Worker's Comp typically provides for benefits if a worker dies on the job, although accepting those benefits usually excludes the recipient from suing the employer.

Whatever Jen ended up arguing, the case ends with an $85 million settlement. I'm a little confused as to why it's referred to as a "settlement," since Jen also refers to the case having made it before the jury. That would suggest that they went all the way through trial, but Roxxon agreed to settle before the jury returned its decision. That's possible, and it does happen, but it's bizarre that Roxxon would offer so much money as a settlement deal. Were they afraid the jury might return with a $150 million verdict? For one guy whose injuries are personal problems?

Even $85 million is rather excessive. If Dan Jermain is dead, then Worker's Comp wouldn't have paid anything remotely close to that. And a normal wrongful death claim wouldn't have wrought a recovery that big. If he's alive and just suing for the negative impact on his personal life, then how could anyone reach a number that huge for what's basically a claim of emotional distress and marital troubles?

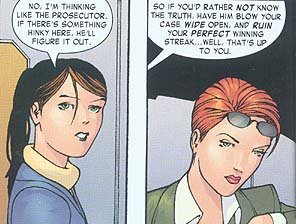

Jen says that she won by suppressing evidence (which can actually be quickly unethical in civil cases like this), and by "turning 'secret identity' shield laws on their head." Shield laws generally apply to rape victims, and the court's willingness to keep the victim's identity out of the public record. But that doesn't mean that the defendant doesn't see his accuser, or that the jury doesn't get a good view of the victim.

She says that all the jury saw of Dan was a "big blue dot on a video monitor." Whatever "secret identity shield laws" may be, I don't see this happening. Back during the infamous William Kennedy Smith trial, the blue dot over the witness' face was seen by television viewers, but the jurors had a full view of the person. Jurors are supposed to be the judges of a witness' credibility, and depriving them of the ability to see a witness' face sorely impairs their ability to do so. And if Danger Man was a plaintiff (which he shouldn't be if Jen pursued the wrongful death route), did they not have him sitting at the plaintiff's table during the trial?

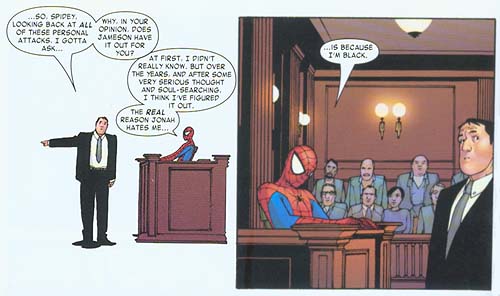

What might Slott have meant when he referred to "secret identity shield laws"? My best guess is that he had in mind the kind of superhero universe judicial policy that allows Batman or Spider-Man to testify as 'Batman' or 'Spider-Man,' in full mask and without having to reveal their true identity to anyone in the court. I know that Bob Ingersoll tackled the possibility of such special protection at least once, and I'll try to dig it up.

Assuming such a law existed, utilizing it here would certainly be turning it on its head, as Jen said. Dan's wife would probably be a party to the case, and both she and his daughter would undoubtedly testify. His name, Dan Jermain, would have appeared in the case name. His testimony would have included a lot about his personal life, both before and after the accident. And 'Danger Man' appears to be little more than a nickname. There's no reason to hide 'Danger Man's true identity, and in fact, aspects of his true identity are all over the case. Having him appear only by video monitor, and blurring his face out, doesn't serve any purpose at all.

So all in all, it's an ingenious legal setup in this issue, but its resolution leaves a bit to be desired.